Diver, 2011. Painted Bronze. 77 x 25 x 11 inches.

Viewing Feuerman’s exhibit Shapes of Reality at Aria Gallery in Florence is the perfect way to spend a summer evening.

The sculptor’s life-size Diver is now on view in the garden at Aria. Diver seeks to capture the motion made by a diver as his body arches, goes backwards, and a ‘C’ shape is formed. This shape represents perseverance and balance as well as the struggle to achieve.

Diver, 2011.

Feuerman sought to accentuate the elegant ‘C’ shape to highlight the beautiful struggle of muscle and body that ensues when a diver pushes themselves past the limits of the ordinary.

As an Artist, Feuerman recognizes the symbol of the diver as a kindred artistic spirit. The Diver is perched on the edge, readying himself for more than just a dive; he is about to create and define his own reality. Feuerman pursues this same bold path with her sculptures.

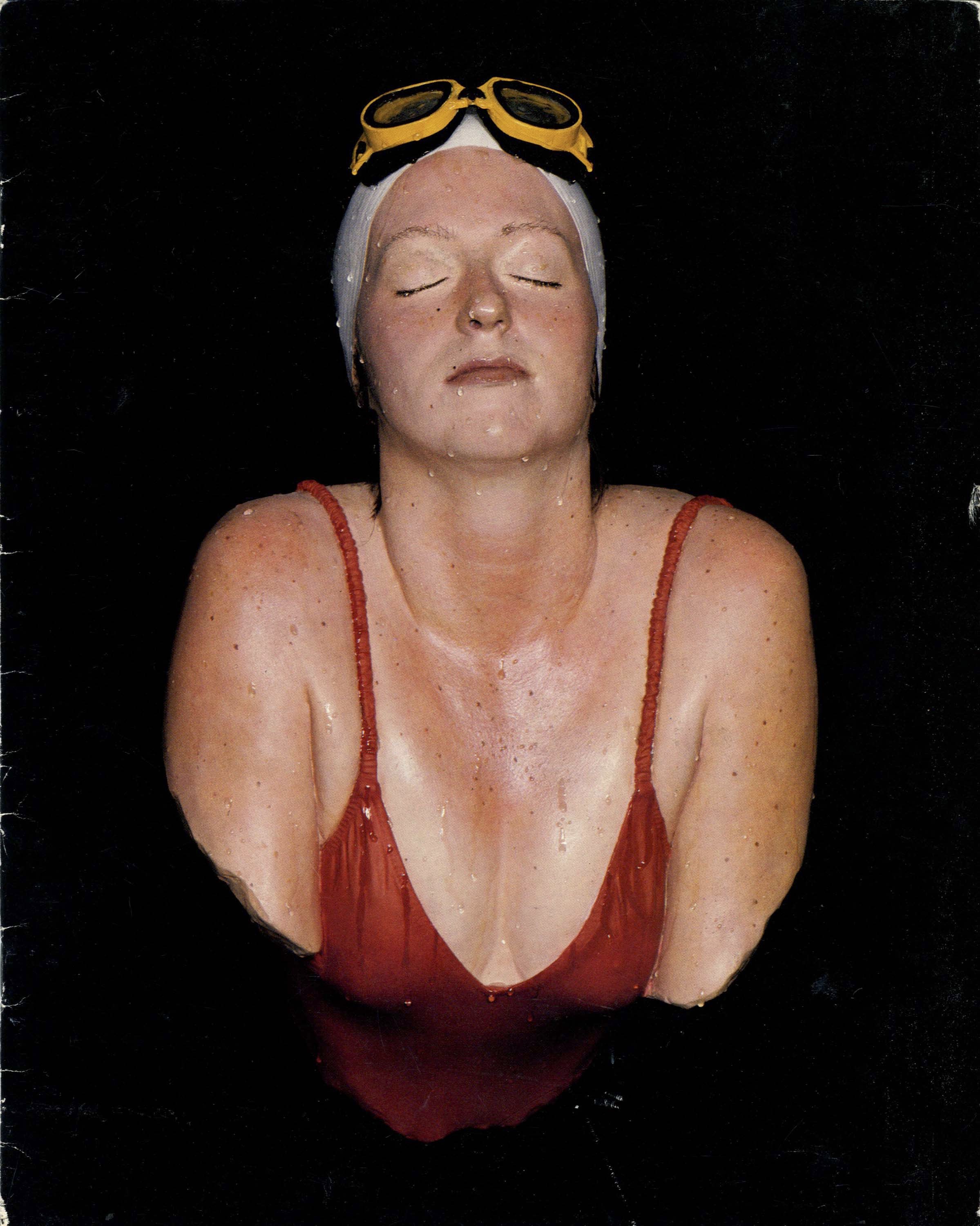

Also on view at Aria Gallery is Next Summer, Monumental Brooke with Beach Ball, Capri as well as Serena Diamond Dust Shower.

Friends new and old, hungry collectors, delighted first-timers, and eager Press toured the gallery of bewitching swimmers.

All were united by the undulating energy imbued in the sculptures. Feuerman’s passionate dedication to detail is world famous and when given the chance, admirers get as close as possible to revel in these sundry specifics.