I’ve been making sculptures for almost five decades. My pieces have been seen around the world since the 1970s. When people see my work, they’re taken aback: children ask their parents if the figures are real people, they don’t know how to react to them, they’ve never seen anything like them.

Like every artist, my work is part of a historical lineage. The art movement I’m associated with is called hyperrealism. The term was first used in 1973 as hyperréalisme by the Belgian art dealer Isy Brachot. The show he put together focused on the American photorealists working at the time, men who made paintings that focused in specific and intimate detail on their subjects to reveal a truth that transcends what a camera can capture.

The term became popular in the following years. Artists like me that were building and painting life-like fiberglass or bronze sculptures came into its fold. The term even reached back into time, and so the canon of Pop sculptures that artists like Claes Oldenburg and Duane Hanson were producing in the 60s and early 70s became part of the lineage too.

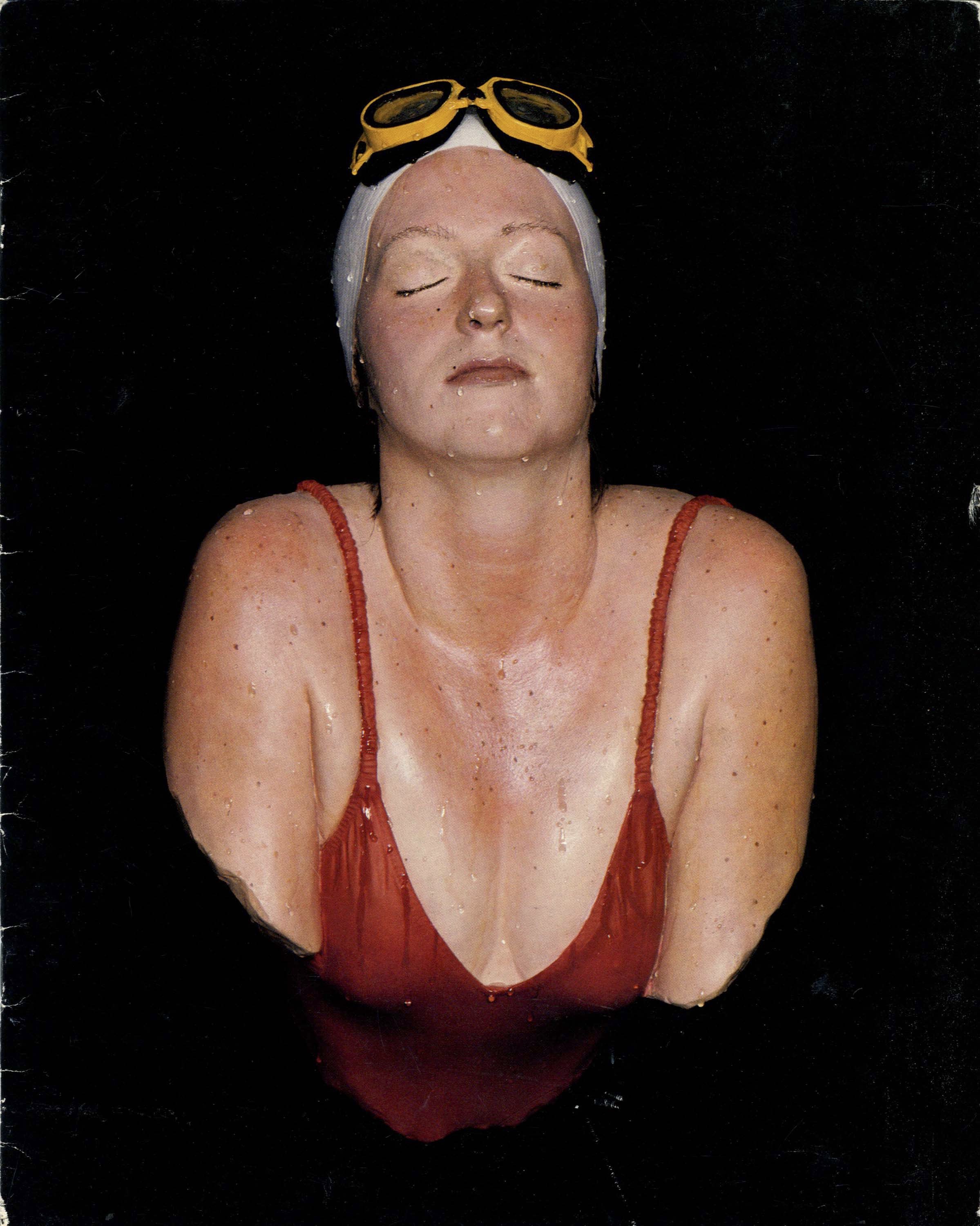

Catalina, 1981

For as long as there has been a thing called “hyperrealist sculpture” I’ve been someone who has shaped and defined the width and breadth of that movement. However, in the production of the history of hyperrealism and even more broadly of life-like sculpture, I have seen my work passed over and reduced while my contemporaries have been elevated.

Institutions like the Met and MoMA have been central players in separating which practitioners become the canon of a movement. Hyperrealism is featured prominently in a show on at Met Breuer right now called Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body (1300-Now). I respect and value the 120 art objects that are included in the show, and in principal I don’t mind that my work doesn’t appear. However, when I went to visit this show recently, it got me thinking about what differentiates my work from those of my contemporaries from the 1970s and 1980s.

So here we go: I think we should talk frankly about the operation of patriarchy in the art world.

Here’s the thesis:

Men’s voices have dominated the industry of art criticism. See Clement Greenberg, see the Royal Academy of Art, etc.

Even when it comes to female subjects, the art that is valued is that which depicts the gaze of male artists. See the ratio of nude women subjects to women artists in the Met’s Modern Art Sections that the Guerrilla Girls made famous: 85% of the nudes are women, while only 5% of the artists are.

Art which elevates the way a woman looks at anything, and maybe especially women, is written out of history. See Romance novels, see Lifetime movies, see the silo-ing of feminist art.

This isn’t shocking to anybody, but I think that it’s worth repeating and considering, and I want to speak to what is lost by dismissing my perspective on female identity.

My sculptures of women are portraits of strength and power and balance. They aren’t an allegory for these things, which of course has been a long staple of the use of women’s bodies in men’s art. Instead, each figure is at a point in her personal journey that has allowed her to recognize these things in herself.

There is a wide functional gap between that depiction and those of my contemporaries John de Andrea and Duane Hanson. Hanson’s figures play with a tradition of satire: they are unhealthy, they have a problematic relation to consumption, they are parodies of the American domestic image that was airbrushed into every magazine of the 1960s. De Andrea’s sculptures have more to do with mine, in that the politics of his figures are less explicit; however he has acknowledged within his own oeuvre the particularity of his perspective, and the centrality of a heteronormative sexuality in his work.

Left: One of Duane Hanson's Supermarket Shoppers. Right: John De Andrea's Allegory, After Coutbet.

This is particularly on display in sculptures like de Andrea’s 1988 piece Allegory, after Courbet. In this work, a female nude figure stands behind and gazes at a clothed male figure, who’s regarding an unfinished sculpture of a woman in his hands. These works are wonderful I think, in that they openly talk about the gendered subjectivity present in all production and consumption of artworks. However, that is a beginning of that conversation, not the end. De Andrea participates in that tradition: male artist, female subject, male gaze, male power.

My art subverts it.

The figures of women I create are not constructed for the male viewer to regard as a symbolic other, but for the human viewer to connect with as the vehicles of their individual lives. Each of them is in a moment that holds their inner strength, their power, and the wisdom that they’ve gained from the challenges they’ve overcome in their lives. I think that’s at the heart of their success in the art market. I also think that if hyperrealism is a tool, then my practice of representing women is an expansion of what that tool can be used for that’s worth noting.

Midpoint, 2017

My pieces don’t confront you with their personhood. They mostly don’t stare out at you and demand a response. That’s because they don’t need your gaze, their dialogue is internal, and that internal reality is something that has been left out of representations of women again and again. I don’t want people to look back at this era of art making and say that the internal reality of women was missing from the practice, but when work like mine and from art makers like me is left out of the canon that is exactly how it will look, and the women artists after me will have to start from scratch again.

That’s the function of the glass ceiling right? My career has been to make this tool for talking about the experience and reality of women, and I want the artists who come after me to have that tool. If I can’t break through into the canon, then they won’t have it, they’ll have to spend their careers inventing it for themselves and then never get to the point where humanity really moves forward, when we’re asking: alright, so what’s next?

—Carole Feuerman